Decolonizing the Academy: Kerry James Marshall’s ‘The Histories’ at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

I: Introduction

Two hundred and fifty-seven years ago, on a winter day in 1768, architect Sir William Chambers visited King George III with a proposal that would reshape Britain’s cultural landscape. Thirty-six artists and architects joined him in petitioning for a society dedicated to cultivating the arts. The result was the Royal Academy of Arts–an institution born of Enlightenment ideals of progress, but inseparable from the British Empire’s expanding colonial project. Its “multicultural” founding members came from Italy, France, Sweden, and America; only two were women, a fact that would not change for another 168 years. From its conception, the institution reflected the exclusions, hierarchies, and epistemic frameworks that characterized the imperial world that produced it.

In 2024, the Academy took a tentative step toward confronting that history with Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now, an exhibition and research initiative that acknowledged the institution’s complicity in sustaining the epistemological and material violences of coloniality*. The Academy did not make a decision to appoint a Black British Royal Academician until 2005, with Sir Frank Bowling, a native Guyanese artist who moved to London in 1953. A much more significant amount of time went by before the Academy publicly recognized how deeply its authority–its ability to determine value, taste, and artistic legitimacy–was shaped by systems of racial, gendered, and class-based oppression. Entangled Pasts was part of a broader cultural reckoning within Britain, a growing willingness to interrogate the very conditions under which its most prestigious institutions came into being.

One year later, Kerry James Marshall: The Histories arrives at the Royal Academy (September 2025–January 2026) as both a landmark exhibition and a profound institutional gesture. The exhibition focuses on a number of series and cycles that Marshall has created between 1980 and now, including a new series dealing with the sensitive, polemical issue of the history of enslavement of Africans, especially made for the exhibition. Marshall was elected an Honorary Royal Academician in 2022, which positioned him not only as a central figure in the arts but as one of the most incisive thinkers of the visual legacies of race, colonialism, and representation.

That the Academy has staged its most comprehensive European survey of Marshall’s work to date suggests a turning point: a moment in which an institution formed through the logics of empire becomes the site of a rigorous visual critique of those very histories. When writing this paper, Walter Mignolo’s concept of epistemic delinking and epistemic disobedience offered a compelling starting point for understanding Marshall’s decolonial commitments. However, it ultimately proved an insufficient framework for capturing the complexity of his practice. Delinking, as theorized by Mignolo, presumes a decisive rupture from Western epistemologies. Marshall’s work, by contrast, persistently stages encounter, negotiation, and critique within Western artistic and institutional frameworks, complicating any reading that positions his practice as a complete epistemic break.

For this reason, this paper situates Marshall’s practice in productive tension between Mignolo’s delinking and Dipesh Chakrabarty’s concept of provincializing. Rather than rejecting Western art history outright, Marshall engages in its genres, scales, and institutions in order to expose their limits, contingencies, and exclusions. In doing so, The Histories demonstrates how decolonial praxis can operate through strategic engagement with Western epistemologies while simultaneously revealing the structural constraints imposed by colonial institutions.

II: The Royal Academy of Arts as a Colonial Institution

Gentlemen,

An Academy, in which the Polite Arts may be regularly cultivated, is at last opened among us by Royal Munificence. This must appear an event in the highest degree interesting, not only to the artists but to the whole nation.

It is indeed difficult to give any other reason, why an empire like that of BRITAIN, should so long have wanted an ornament so suitable to its greatness, than that slow progression of things, which naturally makes elegance and refinement the last effect of opulence and and power.*

Institutions like the Royal Academy affect and influence more than just artists– through education, competition, and education spaces, they mediate between artists, patrons, cultural institutions, public authorities, and public opinion; therefore, enforcing standards of “taste” and “elegance”. Sir Joshua Reynolds’s address to the Academy makes this logic explicit. Celebrating the accomplishment of such an institution as a national achievement, rather than merely as a space for artistic cultivation, but importantly a civilizational marker, an “ornament” cementing Britain’s imperial stature.

His language and rhetoric situate the “Polite Arts” as the natural culmination of empire, presenting aesthetic refinement as both the reward and the proof of a larger political and economic power. In doing so, Reynolds articulates the foundational values of the Academy: that artistic value, taste, and legitimacy are ultimately inseparable from the authority of the nation-state and its imperial ambitions*.

Institutions like the Royal Academy operate not only as sites of artistic production and cultivation but as epistemic mediators. As Walter Mignolo argues, “economy and politics are not transcendent entities but are constituted through and by knowledge and human relations*.” Through mechanisms such as education, exhibition-making, and accreditation, imperial power translates directly into the conditions under which art becomes legible as history and culture. In this way, the Academy functions less as a neutral arbiter of artistic excellence than as an instrument through which imperial logics are naturalized and reproduced. Colonial power exceeds the material and physical realms, extending into what can be understood as epistemological colonization– a complete and total regulation of what may be seen, studied, and valued.

The language employed in Reynolds’s address, phrases such as “so suitable to its greatness” and “slow progression of things,” is undeniably the language of the Enlightenment and modernity. Under the Royal Academy, aesthetic refinement is cast as the triumph outcome of imperial power, positioning European cultural forms as both the norm and the measure of artistic achievement. It is precisely this rhetorical coupling of progress, universality, and cultural authority that grounds what Mignolo, building on Anibal Quijano, conceptualizes as the modernity/coloniality matrix. Within this framework, the Royal Academy as an institution is inseparable from the colonial logics that sustain it, giving rise to the decolonial imperative to “delink from the rhetoric of modernity and the logic of coloniality.”

III: Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now

Historically, the Royal Academy has enforced standards of taste that are aligned with Eurocentric, racialized, and gendered hierarchies. What appears as neutral cultivation of artistic excellence is, in fact, the reproduction of a particular worldview, one in which Western artistic traditions are positioned as universal, and others are understood as peripheral or invisible. It is precisely this epistemic authority that renders the Royal Academy a charged site for decolonial intervention. While recent initiatives such as Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now, suggest a growing institutional awareness of colonial entanglement, they do not fundamentally dismantle or attempt to deconstruct or delink, as Mignolo believes necessary, from the structures through which knowledge and value are produced.

Apollo Magazine, in their review of the exhibition, describes Entangled Pasts as “an attempt to tug at the threads of its own complicated history.*” Featuring eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings alongside contemporary postcolonial works, the exhibition collapses historical temporalities in a move that momentarily positions the Royal Academy as both historical object and contemporary agent. This merging of past and present ultimately arrives at the same conclusion: that the institution remains deeply entangled in the legacies of colonialism and empire that shaped its formation. Rather than resolving this tension, the exhibition renders it visible, staging a self-reflexive encounter that stops short of structural transformation or, as Lorde puts it, a dismantling.

A similar ambivalence emerges in The Art Newspaper’s discussion of the exhibition catalogue, which frames its central question as: “What does it mean for the Royal Academy to stage an exhibition in 2024 that reflects on its role in helping to establish a canon of Western art history within the contexts of British colonialism, empire and enslavement?” In responding to this question, the catalogue quotes Audre Lorde’s 1979 essay assertion that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” raising doubts about whether institutional critique can meaningfully undo the structures that precisely sustain it. Yet the authors ultimately suggest that the exhibition may, in a way, be operating against Lorde’s warning–using the Academy’s own tools to expose, rather than conceal, the histories that have brought the Academy to be and continue*.

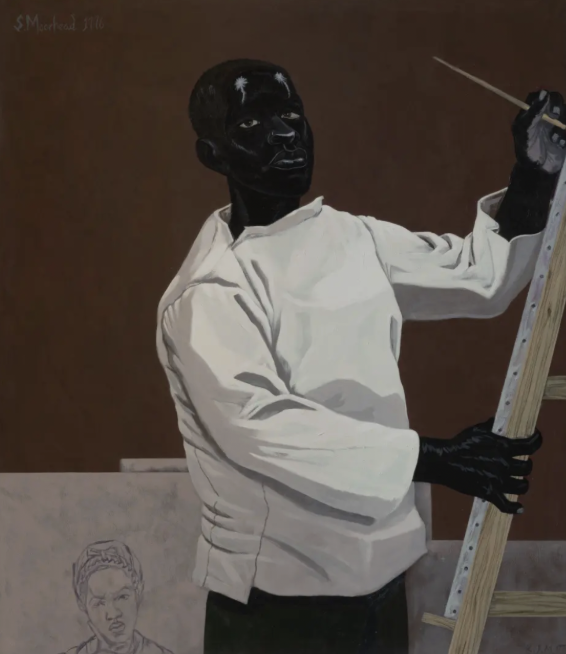

This unresolved contradiction is precisely what renders Entangled Pasts, 1768–Now a critical precursor to Kerry James Marshall: The Histories. It is important to note that Marshall’s work was itself included in the former– Scipio Moorhead, Portrait of Himself, 1776 (2007), which functioned as one of the exhibition’s most incisive interventions*. The painting gives visual form to the historical existence of Scipio Moorhead, an enslaved artist whose life and work have largely been erased from the art historical memory except for a dedication in a poem by Phillis Wheatley. Marshall depicts Moorhead mid-action, painting in front of the easel, brush held in his left hand while the other steadies the canvas, more than a simple positioning or pose, it is an acknowledgement of ownership of authorship with works that went dismissed. His gaze is direct, restrained, and unexpressive, meeting the viewer with an intensity that resists both sentimentality and spectacle. Unfinished portraits populate the background, evoking not absence but interruption. In rendering Moorhead as both a subject and artist, Marshall insists on Black artistic authorship within a canon that has systematically denied it.

This sentiment, especially entering the Royal Academy, is what initiates the larger exhibition by Marshall. Entangled Pasts, 1768-Now demonstrates both the necessity and insufficiency of institutional self-critique, the wider problems of inclusion vs institution deconstruction and reconstruction, revealing how colonial power persists even as it is named. It is within this space of tension, between acknowledgment and transformation, that Marshall’s exhibition intervenes, complicating the question of whether decolonial praxis must reject institutional frameworks altogether or whether it can strategically inhabit them in order to provincialize their claims to universality.

IV: Delinking vs Provincializing

This paper addresses ongoing debates within decolonial theory by examining the limits of delinking as a framework for understanding contemporary artistic practice within Western institutions. While Walter Mignolo’s concept of delinking has been central to decolonial critique, particularly within the Modernity/Coloniality/Decoloniality framework, his theoretical model ultimately falls short when confronted with the material and institutional conditions of contemporary art. Mignolo’s contributions–especially his articulation of epistemic disobedience and his call for rejection of Eurocentric epistemes and knowledge systems–remain productive for this paper insofar as they foreground the political stakes of knowledge production. Yet these interventions are also marked by contradiction.

Mignolo, alongside other decolonial thinkers, has been subject to sustained critique for advancing theories that call for dramatic and total epistemic ruptures while remaining embedded within Western academic and institutional structures. As Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò cautions, the ubiquity of “decolonization” today indicates that either the idea packs an explanatory and/or analytical punch like no other, or it has simply become a catch-all trope*. This tension between radical critique and institutional entanglement forms the central problem this paper seeks to address, positioning Marshall’s practice and his exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in conversation with the decolonial sentiments with which it is often associated, while examining his work in tension with the limits of delinking and provincializing.

In an interview with art historian Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Marshall rejects the common characterization of his work as “anti-modernist,” instead emphasizing that he approaches classical, modernist, and even postmodern traditions on equal terms, describing himself as a “radical pragmatist*.” Marshall’s practice neither fully ruptures from the Western canon nor aims at simply reproducing it. Rather, it operates in a productive tension between delinking–not from the medium of painting itself or the Royal Academy as an institution, but from the epistemic structures that have historically governed them–and what Dipesh Chakrabarty terms provincializing.

In the introduction to Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Chakrabarty makes explicit that “provincializing” Europe is not about directly rejecting or discarding European knowledge as we know it, but rather that “European thought is at once both indispensable and inadequate in helping us to think through the experiences of political modernity in non-Western nations*” The task of provincializing Europe, then, is to interrogate how these inherited ideas and ways of knowing, which have become a shared global heritage, can be reimagined. In this, Chakrabarty inserts a plural view and understanding of Europe, which appears differently depending on the specific histories of colonization in different nations/regions. Unlike Mignolo, who interprets Europe as the embodiment of modernity and therefore sees it as necessary for former colonies and their inhabitants to delink directly from its epistemic structures, provincializing Europe rather emphasizes an engagement rather than complete rupture, seeking to decenter European thought while recognizing perhaps one’s own entanglement with it.

Within institutional critiques of the Royal Academy, this framework is particularly interesting. Museums, academies, and archiving at their core are understood as colonial technologies that structure knowledge hierarchically– delinking thus offers a language for rejecting the authority of these institutions altogether, but perhaps this term serves much more in the poetry of decolonial movement than that of decolonial praxis. When applied to artistic practice– particularly the visual arts– delinking risks being too abstract of a concept to grasp any practical, meaningful response. The demand for a complete rupture– a destruction of the master’s house– presumes a position outside Western epistemologies that is difficult, if not impossible, to occupy, particularly within institutions such as the Royal Academy and Western historical genres as Marshall employs. Artists who exhibit, teach, or circulate within these spaces are necessarily entangled in the very structures they may seek to critique, making it nearly impossible to envision what it might look like to delink from such an institutionally guided field. Mignolo's decolonial approach flattens the complexity of how artists negotiate power, history, and visibility.

This critique, however, does not dismiss delinking’s political urgency. To insist that decolonial art must fully abandon Western forms, references, or institutions risks reproducing another form of rigidity– what Chakrabarty, after Leela Gandhi, has aptly called “postcolonial revenge,” one that undervalues hybridity, contradiction, and historical negotiation. In Marshall’s case, such an approach limits our ability to account for how his work functions aesthetically and conceptually. His engagement with European painting traditions, academic portraiture, and museum display does not signal epistemic compliance; rather, as he sees it– his practice evaluates and experiments with “Power in the sense of an arresting presence” Marshall, affirms that his practice is not one of the production of images which incite empathy for the subject of his work but it rather focuses in making an irresistible presence*.

Chakrabarty’s concept of “provincializing” Europe offers a much more flexible framework for understanding Marshall’s engagement with the Academy and Western historical painting as a genre. Unlike delinking, provincializing does not call for the rejection of Western epistemologies but for their decentering. Marshall’s practice of asserting presence and placing black figures unapologetically into the canon fits the framework as it reimagines genres that once sought to displace and erase marginalized figures. Under Chakrabarty, these Western frameworks remain operable, but are stripped of their claim to epistemic universality. In the case of the Royal Academy as an institution, it continues to be a site for communion but not legitimization. Provincializing thus allows for a critical inhabitation of the canon–one that acknowledges its power and influence yet reveals its limits and the origins of such.

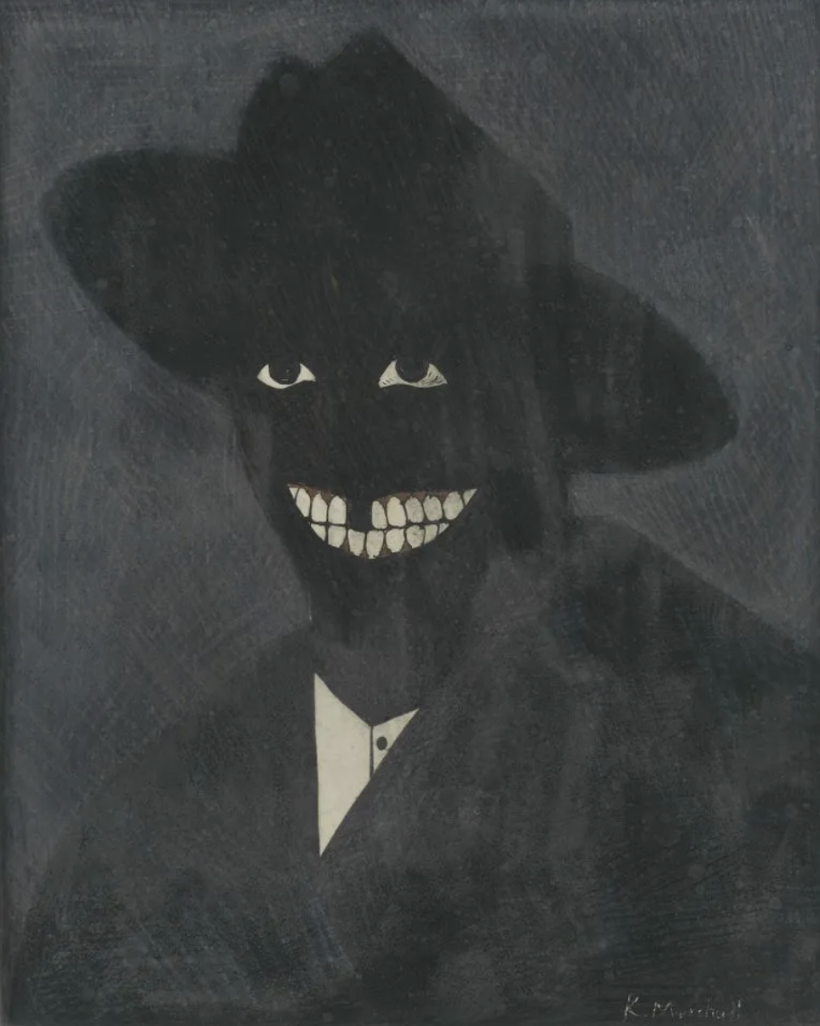

This distinction is crucial for analyzing Marshall’s practice. Rather than positioning himself outside art history, he works within it, mastering its forms. He resists categorization, operating from a position that is neither fully peripheral nor completely assimilated– opening a new plane of its own. When asked about his work, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980, which is in direct dialogue with James Joyce’s novel, Marshall elaborates that the “shadow” aspect: “ represents my escape from the limitations and the projections that accompany stereotypical representations of Black people. It’s my way of saying you can’t continue doing that, and I won’t be subject to it*.” This statement underscores how his practice simultaneously inhabits and critiques the canon, asserting agency within Western art forms while exposing their historical exclusions.

By inserting Black subjects into genres that historically excluded them, and utilizing genres like history painting, portraiture, and landscape, Marshall renders the canon visible as a constructed and exclusionary system, critiquing and at once envisioning an optimistic future. This turn towards futurity and his work, which is deeply influenced by that of science fiction as a genre, his work aligns more closely with provincializing. Kerry James Marshall: The Histories operates between two approaches and arrives at a time where decolonial praxis itself is an abstract concept, yet is able to reveal the limits of both delinking and provincializing when taken in isolation.

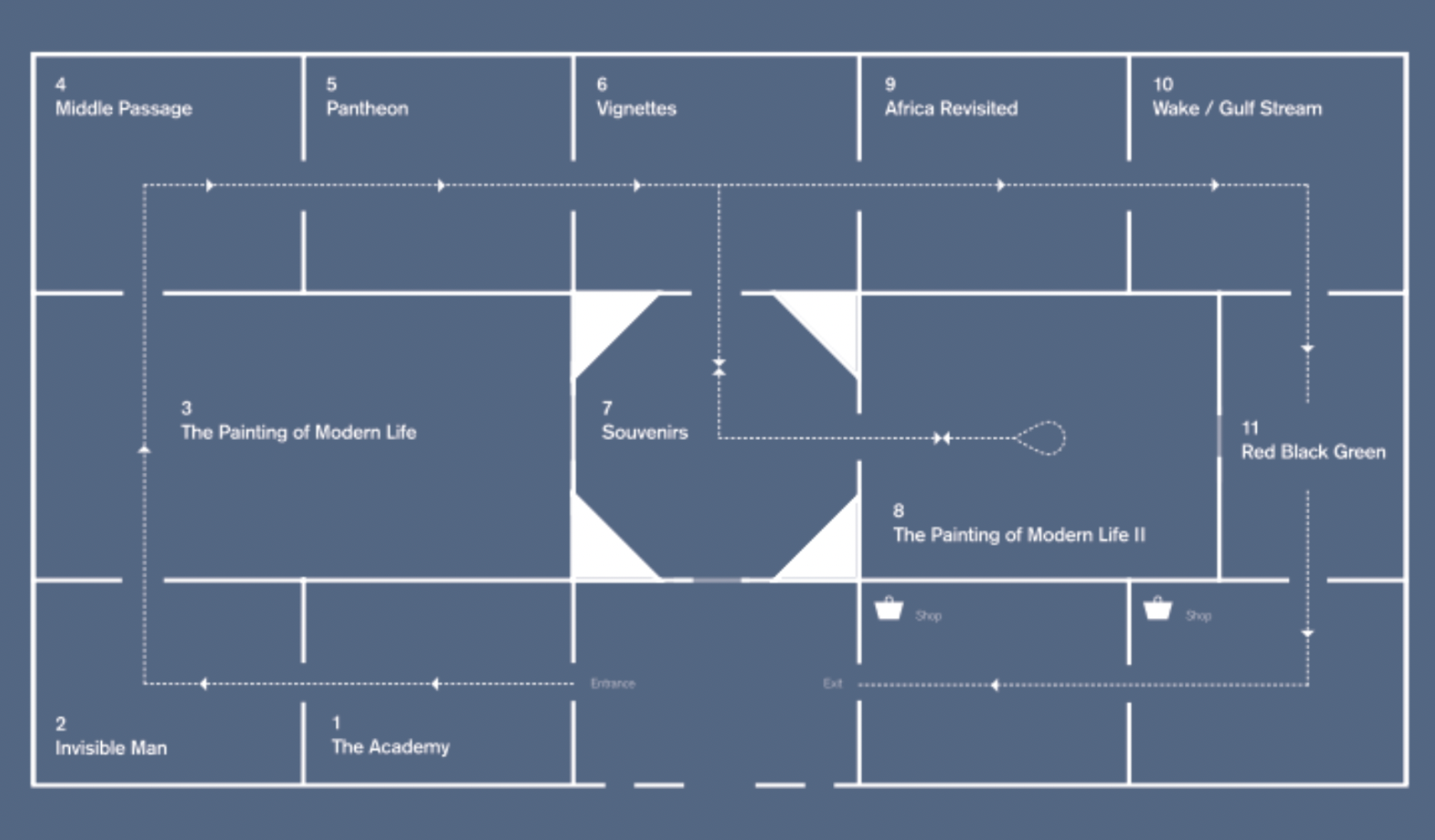

V: Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories is organized across several galleries at the Royal Academy, with a carefully considered spatial and thematic arrangement that guides viewers through both historical and contemporary engagements with the Western canon on behalf of Marshall, tracing over half a century of work. For the purposes of this paper, I rely on the exhibition floor plan as provided by David Zwirner Gallery, which co-represents Marshall, to understand the curatorial strategy, with careful consideration of the added layer that the curation, sequencing, and placement of works has on the paintings and representations of Marshall’s overall work. This approach allows for an analysis of how the exhibition negotiates the Academy’s institutional frameworks, highlighting the ways spatial design contributes to the interventionist character of Marshall’s work.

The exhibition opens with its first room on the left, named “The Academy,” which focuses on the deep fascination of Western art with the idea and image of the studio. The room features works in which Marshall inserts black figures in the studio not solely as subjects but as agents of the rendering of their histories. The mastery of painting as a medium becomes an important motif throughout the paintings, which are deeply intentional in sequence to showcase visibility in more than its common form. The mastery is in his own act of giving the paintings complex color and dimension, in his black figures, there’s profound complexity, which he responds to by saying, “if you say black, you should see black*.”

The second room takes its title from one of Marshall’s key literary inspirations for A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self–Invisible Man. Marshall studied at the Otis Art Institute, where he received his BFA in 1978, at a moment when many artists were abandoning traditional painting. Some artists associated with the Black Arts Movement at the time were distancing themselves from European art traditions completely, making explicit political work aimed at uplifting and protesting. Marshall, however, chose a different path. He continued to pursue mastery of Western art genres, which has always been his vision, understanding their historical weight and technical authority. As the exhibition text notes, under the portrait, this knowledge was accumulated strategically: “When the time was right, these could be put to effective use.”

Marshall identifies Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) as a pivotal influence during this period. The novel influenced a series of works in which Black figures are rendered against dark, nearly obscured backgrounds, producing an effect of near invisibility. This visual and technical strategy in portraiture functions both metaphor and critique. The figures are present yet difficult to perceive, echoing Ellison’s exploration of social invisibility while exposing the conditions under which Black subjects have been rendered unseen within Western canonical genres. Marshall inhabits its conventions in order to reveal their limits, provincializing the hierarchy and historical legacy of the portraiture genre, criticizing the long-endured absence, erasure, and complicated politics of visibility for black subjects.

The following room, “The Painting of Modern Life,” focuses on Marshall’s exploration and influence of canonical figures like Édouard Manet and Georges Seurat, who turned Marshall’s focus to history painting. The rendering of modern life by these nineteenth-century painters is perhaps the modernity/coloniality matrix Mignolo seeks to delink from, the epic scale of these paintings is an integral part of their historical ability to picture modern life, somethin Marshall works with to his advantage, like Seurat and Manet, Marshall began his exploration of the form with a desire to explore the technical and thematic possibilities of modern life, especially in terms of scale which for Marshall would demand a different type of engagement and attention from the viewer.

The fourth room is dedicated to “The Middle Passage,” featuring five works that to address the history of the transatlantic slave trade for which no depiction other than the recording in colonial history texts exists. In the paintings, he makes the connection to Africa not only visible but deeply entrenched, even in materiality, to the histories he is depicting, incorporating symbols and diagrams derived from Yoruban religion, Voodoo, and other syncretic religions across the African Diaspora. In the fifth room, the focus shifts to the forgotten, erased, and unaccounted-for black slave rebels, poets, abolitionists, and activists, in a series of portraits like the earlier discussed portrait of Scipio Moorhead. The following room further explores complex themes that the Western art historical canon has long claimed. In “Vignettes,” he approaches the subject of romance, challenging the trivialization and oversimplification both technically and literally. He is playing with the tension of the notion of agency, love, birth, and nature.

The exhibition, which thus far invites the viewer to move around the Academy in a clockwise motion, directs visitors to the middle for “Souvenirs,” where addition to painting, Marshall’s form experiments with sculpture, video, and print. This room takes after some of the works in his 1998 exhibition Mementos. The four paintings reunited in the room survey the decorations existing in different sets of homes, which look at figures of political and activist martyrs such as Martin Luther King and the assassinated Kennedys. The next room, which is of identical size to the first iteration of “The Painting of Modern Life”, hosts its second, this time placing in conversation works from the 60s with late 2010s. Marshall’s ability to play in such scale with the historical landscape and modern life painting genres is a true testament to the possibilities “provincializing” these implies, decentering its previous understanding and existence into a new re-imagined medium. In this room, the famous School of Beauty, School of Culture, 2012, a sister work to his earlier barber’s shop painting De Style, depicts the beauty shop as a lively place where black women get to reimagine and remake themselves, yet continue to be challenged by Eurocentric ideals of beauty simultaneously– resulting in a complex exploration of the “black romantic pictorial tradition” and refusing the narrowing of the lived experience of these communities into aesthetic and political touchstones.

The last three rooms, much smaller and identical in size to the original first few, explore varying themes yet as much of his work they all coexist and deeply inform and influence each other; “Africa Revisited” an exploration of challenging moments in the recorded history of Africa, including the slave trade which he continues to render and visualize in “Wake/Gulf Stream” adding complexity by inserting other dimensions of black experience like “achievement” as a motif in his images and finally “Red Black Green” which uses the colors of the (Universal Negro Improvement Association) or Pan-African flag as a thread in his paintings, celebrating black nationalism and celebrating a return and reconnection to Africa, continuing to place black figures at the center of his narrative focus and leaning into visions of the future by doing so asserting Presence, “with a capital P*.”

VI: Conclusion

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories does not offer a clean resolution, nor is it trying to answer the question of how decolonial praxis should operate within Western institutions. Nor does it pretend to dismantle the Royal Academy’s colonial foundations in the absolute. Instead, the exhibition works very similarly to Marshall’s practice– leaning into complexity and hybridity.

This paper concludes that Walter Mignolo’s framework of delinking–while politically urgent–proves insufficient for understanding Marshall’s practice as it unfolds within the Royal Academy and therefore brings into question its ability to bring forth decolonial praxis in the present day. To insist on rupture alone risks abstraction, flattening the complex negotiations which Marshall intricately investigates in this large survey: visibility, mastery, and power. Dipesh Chakrabarty’s concept of provincializing Europe offers a more productive lens at this time to envision an imaginable and deeply influential decolonial praxis. Rather than rejecting Western epistemologies, provincializing exposes their historical colonial legacies and strips them of their claim to universality. Marshall’s sustained engagement with Western genres of history painting, portraiture, landscape, etc, does precisely this work. By placing Black figures unapologetically at the center of these traditions, he reveals the canon as a constructed system which is able to, unlike posed by Audrey Lorde, can be, in fact, a tool if imagined, rather than purely a neutral inheritance.

The ultimate strength in an exhibition of the caliber of The Histories lies in its ability to hold these tensions open rather than resolving them, insisting that decolonial praxis is perhaps not a complete process but an ongoing negotiation. In occupying space and rendering Presence, Marshall demonstrates that the most incisive critiques of empire may not come from outside its walls, but from within.

*—

Reynolds, Discourses, DI, p.13, 11.I-9.

Holger Hoock, “Introduction,” in The King’s Artists: The Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture 1768–1830, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199266265.003.0001.

Walter Mignolo, “The Conceptual Triad”, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, 136.

Walter Mignolo, “The Conceptual Triad”, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, 139.

Arjun Sajip, “The Royal Academy Reframes Its Past,” Apollo Magazine, accessed December 17, 2025, https://apollo-magazine.com/entangled-pasts-colonialism-art-royal-academy-review/

Beth Williamson, “Catalogue for Royal Academy’s ‘Entangled Pasts’ show unpacks the institution’s problematic past,” The Art Newspaper, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/03/12/catalogue-for-royal-academys-entangled-, pasts-show-unpacks-the-institutions-problematic-past.

“Start here: Entangled Pasts, 1768–now,” Royal Academy, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/start-here-entangled-pasts

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, “Introduction,” Against Decolonisation Taking African Agency Seriously (2022), 15.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, ed. Mark Godfrey (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2025), 10, https://fileshare.davidzwirner.com/dl/6qmdf7TJFQ9T.

Dipesh Chakrabarty, “Introduction,” Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 16.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, ed. Mark Godfrey (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2025), 12, https://fileshare.davidzwirner.com/dl/6qmdf7TJFQ9T.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, ed. Mark Godfrey (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2025), 13, https://fileshare.davidzwirner.com/dl/6qmdf7TJFQ9T.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories Exhibition Floor Plan (PDF), David Zwirner, accessed December 17, 2025, 4-8, https://fileshare.davidzwirner.com/dd/4wvX9HtbfJ4H.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories Exhibition Floor Plan (PDF), David Zwirner, accessed December 17, 2025, 11, https://fileshare.davidzwirner.com/dd/4wvX9HtbfJ4H.