Temporalities of Memory and the Making of Garifuna Futures: The Music of Aurelio Martínez

Every summer, my family and I traveled from Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, to Roatán, an island located about 65 kilometers (40 miles) off the country’s northern coast. It was an island that, despite becoming part of Honduras in 1859, seemed to possess a life, a history, and a people of its own. My mother loved Roatán because it reminded her of St. Lucia, where she had studied abroad during her teenage years. She especially cherished speaking with the local Garifuna community, whom she came to know well over the years. Summer after summer, the same locals would be there on the beach, despite the capitalist and neocolonial attempts to dominate and exploit the island for its rich culture, natural resources, and tourist economy. Resistance is deeply embedded in their history, and it lives deep in their memory, traceable back hundreds of years.

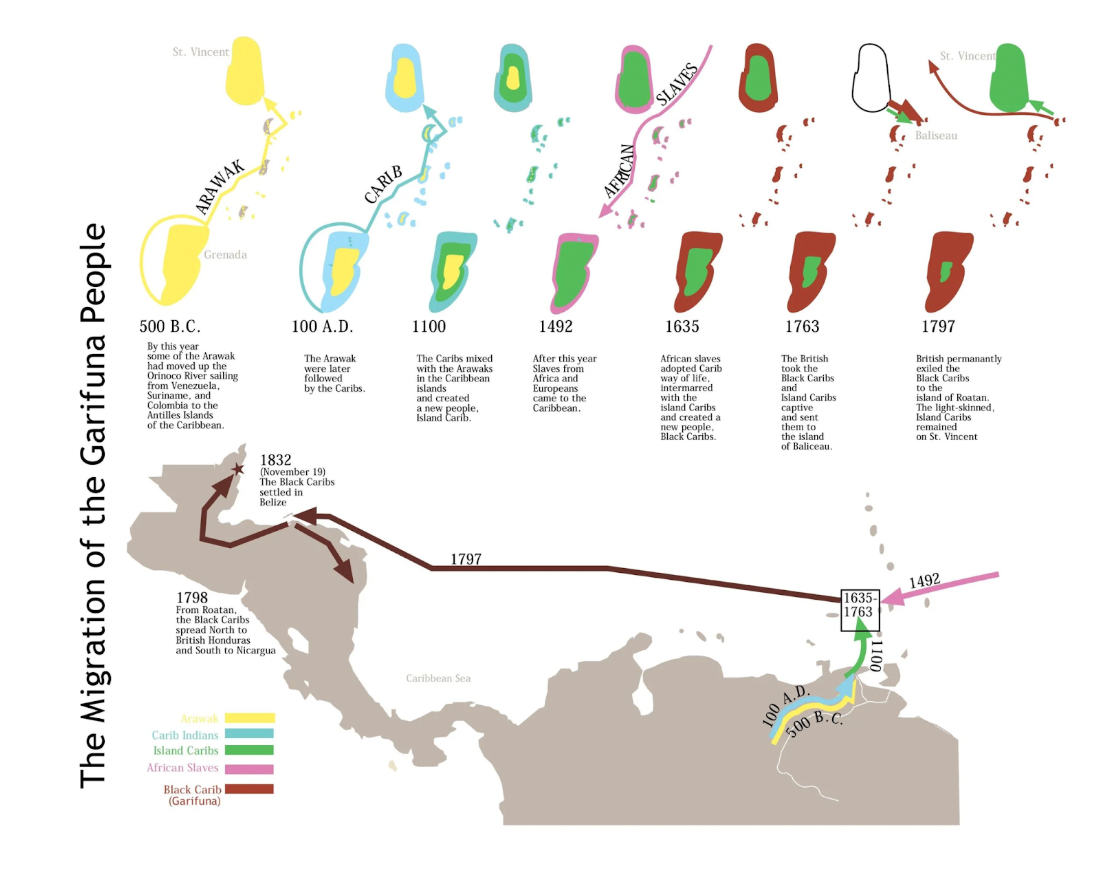

The Garifuna people are descendants of West African slaves who “washed ashore” on the Caribbean island of Bequia (now St. Vincent and the Grenadines) in the seventeenth century, while being transported to plantations in the so-called “New World.” Upon arrival, West African slaves and the island’s Indigenous Kalinago (Carib) people started families, making a new Afro-Indigenous culture. They are often referred to as “the Black Caribs,” and though commonly referred to as the Garifuna, they refer to themselves as the Garinagu, Garifuna being mostly used to describe both the language and culture of the group*. The Garifuna became known as the “fighting Caribs” because resistance was central to their history: they not only escaped slavery but also fought European colonization and imperialism for over a century. This led Britain and France to agree in 1748 to regard St. Vincent as “neutral,” thereby acknowledging the island as Carib territory. That lasted until 1763, when the British started the sale of land for plantation purposes, particularly that of sugar*. The Carib and Garifuna challenged and resisted colonial powers until 1797, when the Garifuna were militarily defeated by British forces. Thousands were subsequently exiled to the Bay Islands of the Caribbean, starting at Roatán and then migrating to Belize and the coastal regions of Nicaragua and Guatemala.

In this essay, I aim to explore the history and narratives of origin, as told and preserved by the Garifuna community. Their history, marked by displacement, resistance, exile, and adaptation, offers a compelling lens through which to examine how memory operates under colonial and imperial pressures. This paper applies Maurice Halbwachs’s ideas about memory as a collective act and Paul Connerton’s subsequent claims of collective memory as something organized and legitimized through performance and bodily practice. Additionally, I will be looking at Enrique Florescano’s ideas around myth as historical consciousness– in order to fully grasp how Garifuna communities have rendered their histories through art and performance.

In exploring Garifuna thought and collective memory, it becomes essential to consider how these memories are situated across space and time. For this reason, I focus on the music and performance of the late Garifuna leader Aurelio Martínez (1969–2025). I approach his work as a critical text, with careful consideration of the limits of time, place, and personal experience that shape both his artistry and my interpretation of it. My decision to center his work stems from his widespread acclaim–within Garifuna communities, the Caribbean, throughout the African diaspora, and globally–which I read as evidence of its resonance in articulating a shared experience and understanding of Garifuna heritage and memory. By placing his body of work in conversation with the theoretical frameworks provided by Connerton, Florescano, and Halbwachs– I seek to understand the memories, myths, and histories of the diverse Garifuna community, more importantly– I aim to gain a comprehensive understanding of what Garifuna memory in the face of colonial and modern capitalist exploitation remembers– how it does, and how their engagement with history informs Garifuna futurity. This essay examines how Garifuna mythmaking, oral history, and embodied traditions function as resistance to colonial erasure and oppression. Furthermore, it questions whether Western epistemologies of memory alongside colonial renderings of Garifuna existence, resistance, and identity fully capture the decolonial dimensions of Garifuna thought.

i: We Ought to Be Like the Pelican: The Music of Aurelio Martínez

“250 años que la comunidad garífuna llegó a Centroamérica. ¿Su primera comunidad? Roatán, Punta Gorda. Luego se cruzaron a Trujillo, Guatemala, Belize, Nicaragua. Este pueblo representa la resistencia a partir de la esclavitud, a partir de África, pasando por el Caribe, y resistencia todavía por Centroamérica, especialmente en Honduras. Danos tiempo, danos tiempo a quedarnos aquí en casa*.”

- Aurelio Martínez

It was a national shock when, just this March (2025), the tragic death of Aurelio Martínez saturated the news in Honduras. Martínez was born in 1969 and was considered a cultural ambassador of the Garifuna nation. He was a songwriter, performer, and the first Garifuna politician in Honduran National Congress. He was highly esteemed both nationally and internationally for carrying the culture and legacy of one of the world's richest indigenous groups. Music is an interesting medium because it is always a conversation. One between artist and listener, songwriter and band, ancestor and descendant, past and present, individual and collective. With this holistic reading of music, Halbwach’s ideas about our recollections being “dependent on those of our fellows, and on the greater frameworks of society*” bear real weight.

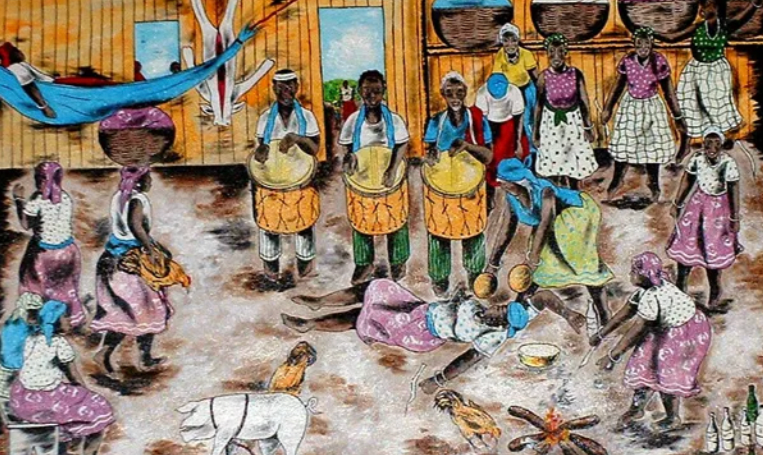

In a 2022 performance for NYU’s Hemispheric Institute, Aurelio Martínez brought Garifuna music traditions to a contemporary landscape, following the current and ongoing discourse of preserving indigenous histories and culture– transforming the stage into a site of memory–a space where colonial legacies were confronted, and communities converged. Through his instruments–voice, percussion, and guitar–Martínez not only performed songs but enacted the larger history of a collective experience while inviting new audiences into its rhythms and stories. His shows are composed of different elements: guitar (both acoustic and electric), which he recalls engaging with as a kid, making his own out of cans, sticks, and fishing line; the primero and segunda drums (high- and low-pitched Garifuna traditional drums); maracas (a traditional instrument with links to the Caribbean and South Americas); and conga drums (first linked to Cuban people of African descent, representing the connection between Africa and Garifuna/Caribbean culture)*. These elements merge more than cultures; they merge temporalities: past and present, the modern and the traditional. In doing so, his performance reminds us that Garifuna music is not simply preserved and carried across time but is alive– continually made, remade, and carried into the future.

Memory poses a threat to imperial power because it refuses the stability that empire depends on. It resurfaces what has been silenced, complicates official histories, and keeps alive the experiences that colonial narratives attempt to contain or erase. Memory is fluid. It moves across generations, across bodies, across performances, and in that movement, it creates openings for alternative histories to emerge.* More than just representing and showcasing Garifuna culture and language, the musical and narrative power in Martínez’s performance lies in the active rewriting, re-making, and cementing of a collective memory and understanding of Garifuna origin, culture, and experience by the Garifuna as opposed to colonial renderings of Garifuna history. Halbwach understands collective memory as a fluid one based on the idea that it changes as societies’ present changes*– this notion implies the possibility for marginalized groups, like the Garifuna–whose histories under colonial and imperialist rule have been wrongfully recorded and disseminated throughout time– in being able to reclaim and re- narrate a collective history of not violence, but perseverance, of not displacement but belonging.

Aurelio Martínez makes an interesting use of an allegory in his performance by saying, “We ought to be like the pelican, the pelican has many homelands, the pelican is free.” In addition to his song lyrics, he has made other comments about homelands: “My homeland is Honduras,” “New York is my new homeland,” “Central America: Garifuna nation, and New York– a new Garifuna nation.” His song and performance are about joy, about history, about remembering a turbulent, violent origin, yet the transformation of that into a rich, powerful, unique, and peaceful culture. In his studies of memory, Halbwach argues that society can cause the mind to transfigure the past to the point of longing for it. While that may be truthful in some cases, in the particular case of Garifuna collective memory, there seems to be more of an openness in remembering without longing for the past while looking forward to a future. The pelican allegory posed by Aurelio in his performance may be a symbol of a collective’s desire not just for freedom but belonging, and a belonging not fixed on one place. There seems to be an acute awareness of the diasporic nature of the Garifuna nation. Based on the conversation, lyrics, and music of Aurelio Martínez, and what one can only assume is thousands of Garifuna people who identified with his work– I believe the larger conversation surrounding Garifuna futures seems to have less of an interest in returning to the past, but a collective longing of remaining in the present and moving towards a shared future– an almost poetic and hopeful last migration for the community.

Tradition preserves collective memory through ritual, repetition, and symbolic acts that transmit shared meanings across generations. While Halbwachs examines tradition primarily in relation to social class, Paul Connerton emphasizes that social memory is maintained not only through written or verbal forms but also through bodily practices–gestures, ceremonies, and everyday routines–which carry histories across generations. The music and performance of Aurelio Martínez exemplify these ideas. Lyrically, his work engages with multiple aspects of memory, particularly the memory of place. Every collective memory is situated within a physical space*, which may explain why song, dance, performance, and writing often render space itself as a space for communal histories. Space endures, while individual experiences and lives are fleeting, the connection to land in indigenous communities also adds complexity in thinking of how space, performance, and instruments add to memory and preserve culture. Consequently, as posed by Halbwach, the past can be remembered only by recognizing the ways in which space anchors collective memory.

ii: An Elegy to the Land : Cyclical and Maritime Temporalities in The Music of Aurelio Martínez

There are Garifuna people who have forgotten their roots

There are black people who forget where they come from

But I will never forget Africa

Sister I will go to Africa to look for our roots

Friends, how many will go with me?*

To understand how Garifuna memory functions, it is necessary not only to consider what is remembered but also how time itself is structured in the act of remembering. Aurelio Martínez’s lyrics reveal layered temporalities—the ancestral, ritual, migratory, and future-oriented—which provide context in understanding how layered Garifuna identities are continually narrated and remembered. These temporalities align closely with the work of Halbwachs, Connerton, and Florescano, all of whom suggest that memory cannot be separated from the temporal frameworks through which communities narrate and legitimize their histories. In Aurelio’s lyrics, these frameworks are not just abstract ideas and theorizations but lived, embodied, and performed notions of time. His music is a site of memory and an even larger act of resistance; it is where history is continually made and remade, and where Garifuna identity resists the linear historical limitations imposed by colonial modernity– ultimately deconstructing the past and asserting presence.

One prominent temporality in Aurelio’s work is cyclical time–a form of temporality that does not move forward but loops, returns, and recurs. In his song “AFRICA”, Martínez alludes to understanding Garifuna origins tied to Africa as a starting point, which is of great significance. The emphasis and understanding of Africa as an origin calls many things into question– for one, perhaps that the Garifuna are yet to collectively unpack their complex history and origins, something Aurelio seems to question deeply: There are black people who forget where they come from/ But I will never forget Africa. The song is a call to the Garifuna people to join a collective questioning of origin, as well as prompting a mythical return: I will go to Africa and look for our roots. Important to note, however, is that the return does not imply a complete one but what one can interpret as a cyclical one: Of Africa oh Africa garifuna roots/ Oh Africa oh Africa our black roots. The song alludes to the return to Africa for a moment of understanding and connection, rather than a migration that seeks to erase the realities of Garifuna complexity, which is its diasporic nature. What Martínez is wrestling with is the erasure of the tie to Africa as motherland, which is often overlooked because of how drastically diverse Garifuna identities are, whether those communities are in Honduras, Belize, St. Vincent, or New York– the identification of Africa would, as suggested by Martínez, mark a collective thread amongst the Garifuna diaspora.

Connerton argues that collective memory is preserved through bodily practices and ceremonial repetition, which create fixed frameworks through which the past is continually reactivated and informs the present and future. This idea resonates deeply in the Garifuna musical tradition and in the lyrics Martínez performs. In songs such as “DÜGÜ”, whose English translation is interpreted as “family reunion”, the refrain “Shake your maracas” functions as a ritual call, echoing the communicative structure of Garifuna dügü ceremonies, which is done with the purpose to appease the ancestors, make them happy, and heal the living of illnesses and other adversities which are believed to happen if not performed. By doing this, Martínez links the performance aspect directly to memory and the past, opening a dimension in the present and thinking already about future implications/repercussions, performing cyclically. As Connerton theorizes about social memory, “we are likely to find it in commemorative ceremonies; butcommemorative ceremonies prove to be commemorative only in so far as they are performative*.” These ceremonies summon ancestors not as figures of the past but as active presences in the communal now.

Here they come! Oh, they have arrived!

The ancestors are arriving

Martínez’s lyrics operate the same way. They do not describe memory from a distance; they perform memory. The repeated invitation to gather creates a collective present where the ancestors return, where the living and the dead coexist, and where song becomes the ink through which history is textualized. This cyclical temporality resists Western constructions of history as linear progress or decline. Instead, it creates a decolonial temporality rooted in continuity and return.

Alongside cyclical time, Martínez’s lyrics articulate another temporality that emerges from the histories of displacement and constant movement that have shaped the Garifuna people: a maritime/migratory temporality. The sea appears throughout Martínez’s lyrical material as it reflects Garifuna history as both a site of trauma–forced displacement, exile, and of possibility and futurity. The ocean and ties to the sea become a temporal compass where past journeys and future movements coexist. In “DARANDI,” “LARU BEYA,” and “YALIFU,” Martínez sings of the sea and especially of “those who leave in search of a better life,” invoking the long histories of migration– possibly much contemporary migrations– from St. Vincent to Roatán, and from Central America to the United States. The temporality here is neither nostalgic nor fatalistic. Instead, it names migration as a condition, one that shapes and informs Garifuna pasts, presents, and futures. The sea here becomes a witness to this cyclical movement and an archive of memory.

You went away in search of a better life

To the sea and found the death (DARANDI)

At the seashore, at sunset

In the silence, I fall asleep

When I woke up, I dreamed

That I love you, I love you (LARU BEYA)

You have not arrived, Father. You have not arrived

I am here on the seashore waiting for you

Father, where are you?

Out at sea, and I am here on the shore (YALIFU)

This orientation toward the future becomes explicit in the song “LANDINI,” where Martínez asks, “What happens here? Every day, our farm is further from our hamlet/ What will we cultivate tomorrow?/ Where will we cultivate cassava to make cassava bread?” There are multiple layers to the questions: agricultural, economic, existential– collective. The future is a theorization of a future for a community whose motion has always been ongoing. As Florescano suggests, mythic narratives often orient communities toward collective futures, providing frameworks through which they imagine themselves*. Martínez’s lyrics function in this mythic register; the uncertainty in “LANDINI” does not register as despair; rather, it reflects an openness to possibility– a consistent tone in his larger project– of a Garifuna futurity shaped not by fixed homelands but still by movement. This maritime temporality therefore destabilizes colonial narratives that sought to confine Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to territories or static identities. His music articulates these different temporalities, which–like the origins of the Garinagu–are diverse and impossible to narrow down. In his work, the sea is not a divisive site but rather a uniting one; it does not separate the Garifuna from their origins but connects them to an expansive, diasporic world. To understand Garifuna notions of origin is to enter a space where history is not fixed but fluid, moving across bodies, borders, generations, and song. The Garifuna have carried with them a memory shaped by disruption and reimagination– a diaspora born of resistance, and a worldview continually rewriting colonial narratives which historically have sought to dilute Garifuna cultures and histories.

Aurelio Martínez’s music stands at the center of this living archive. What emerges from this reading of Garifuna historical consciousness in his music is a refusal of erasure–an insistence on remembering in ways that affirm presence rather than loss. Their mythmaking and embodied traditions reveal a decolonial sensibility that is constantly changing but never forgetting. Martínez’s work, especially, gestures toward a Garifuna futurity grounded in motion, in the idea that homelands can be various and that belonging is not diminished by displacement. In the end, Garifuna memory lives on not because it resists change, but precisely because it adapts, transforms. It is a living, breathing spirit, the memory and collective act of remembering that refuses to be confined or silenced. As Martínez reminds us through the figure of the pelican, Garifuna identity lies precisely in that freedom: the ability to carry across seas, borders, temporalities, and continue.

* ——

Abtahian, Maya, Manasvi Chaturvedi, and Cameron Greenop. “Garifuna.” Journal of the International Phonetic Association 54, no. 1, 2024.

Coser, Lewis A. “Introduction.” In On Collective Memory by Maurice Halbwachs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Connerton, Paul. How Societies Remember. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Florescano, Enrique. Memory, Myth, and Time in Mexico: From the Aztecs to Independence. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

Frishkey, Amy. Standing the Test of Time: Neo–Traditionalism as Neoliberalism in Garifuna World Music: Diagonal (Riverside, Calif.), 2021.

Halbwachs, Maurice. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Hulme, Peter. “French Accounts of the Vincentian Caribs.” In The Garifuna: A Nation Across Borders: Essays in Social Anthropology, edited by Joseph O. Palacio. Belize: Cubola Books, 2005.

Lewis A. Coser. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Lumb, Judy. “Garifuna Dügü: A Really Extended Family Reunion.” Essays. Producciones de la Hamaca, 1996. https://www.warasadrumschool.com/dugu-garifuna-spirituality/.

Martínez, Aurelio. “AFRICA.” Lyrics. Aurelio Music, 2025.

Martinez, Aurelio. Garifuna Homelands. NYU Hemispheric Institute, 2022. https://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/931zd3sq.

Williams, Victoria. “Garifuna.” In Indigenous Peoples: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to Survival. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2020.